Immortal

By nineteen, Chester Charles Almon felt charmed. So much so he dropped his first name in college. At ten, he had been struck by a car when he chased a step ball pinky into the street, but the driver had been cautious on the little street. His broken leg and cracked ribs mended perfectly. As a rebellious teenager, he followed his friend into the abandoned concrete building. He fell through the weak flooring and spent two weeks in the hospital.

Charles expected and did land on the Dean’s List after his freshman semester at State. Later that school year, it came as a distinct shock that his life was not perfect.

College was easier than high school. Not the course material, but with the lack of home drama—his brother not around to fight with father—helped his concentration immensely. No, it wasn’t school that brought him down. It was night clubbing. In the first semester, he accompanied friends only on Tuesdays for drinks at Judges Bar. His fake id gave him entry to a world where drink let cares slip away. However, in the spring term, he ordered beers more school nights than not and often at last call. He drank and sometimes danced. The times he rested to catch his breath seemed as a small price for carefree abandon.

The following mornings, he often woke groggy yet forced himself to 8 a.m. calculus. This continued through May to the day before his June 1st final. He studied with great concentration until 10 p.m. on exam eve, before heading to Judges to relax. The next morning, he struggled to wake up. Crossing the campus, he had to stop multiple times to take deep breaths. At the tennis court bench, he had to sit for several minutes, before he could continue on.

Finally, he opened the classroom door. The exam had already started. The professor shook his head. “Mr. Almon, you’re ten minutes late. You better get right to it.” He handed him the white question sheet and a blue booklet.

Charles opened the question sheet. Reading, his arms hung loose at his side. He couldn’t give them any energy. He gazed at the sheet. He would decide on his approach to each question—and give him time to gather the energy to write out the answers.

Minutes later and still Charles hadn’t raised his pencil. The professor came over. He bent low and whispered, not wanting to disturb other students. “You haven’t started. Is there a problem?”

Charles hated to admit it, but he said, “I don’t have the energy.”

“Are you sick? Do you want to go to the campus clinic?”

“I don’t think I can.”

When the school nurse practitioner arrived, she touched his forehead, counted his frenetic pulse, and called for an ambulance.

In the emergency room, his heart continued to race, one hundred and eighty beats per second. He heard someone say the heart beat before it filled with blood.

It took weeks of total bedrest before Charles’ heart resumed its regular beat. A week later the doctor allowed him to get out of bed. Finally after six weeks, the doctor came to discharge him.

“You must remain on very limited activity. Your heart has not fully recovered. If you do too much, you’ll be back in here and in worse condition than this episode. At home, you may move about one floor and don’t overdo it. No stairs for the first week. After that, you may, but only once a day. That should be the extent of your exercise until your checkup next month.” The doctor pointed at another instruction. “Follow this diet. Especially no alcohol and no caffeine. You have six months to make an important decision. Limit your physical activity—no sports, dancing, or strenuous activity—or get a pacemaker?”

“With the first choice, I might as well be dead. Tell me more about the risks and rewards of the pacemaker.”

A semester passed before Charles had the pacemaker implanted. His increased energy made every day more enjoyable, but sleeping surprised him most. The erratic and skipped beats were gone. No longer did they keep him awake. The steady beat of the pacemaker lulled him better than a childhood lullaby. He returned to college with focus and energy. As a sophomore, he limited his excitement to good meals, TV movies, and board games. His health improved. He studied and resumed his place on the Dean’s List .

~

After graduation summa cum laude, he landed a job at the publicity department for the local mall. He used his energy that once went to energetic activities to hone his language. “Stroll aisles. Satisfy whims. Pleasure favorites.” He enjoyed composing slogans for circulars.

Charles had become cautious, avoiding over-exertion and nighttime activities. The memory of pain slipped from daily thought. When the new boss invited the staff to drink, he went but ordered iced tea. The boss said that she held the same table every Friday for whoever wanted to join her. As that evening wore on, the others order additional drinks, told increasingly stupid jokes, and laughed even louder. Charles slipped away to home.

Several months later, a coworker who drank with the boss became the new head of circulars. Charles stopped at the boss’s table that Friday. After a few drinkless Fridays and fading memories, ice tea transitioned to Mimosa spritzer. A mellow cheer suffused his outlook. Gradually, he started having a drink at home. Once started, since he wasn’t dancing and exerting, he ramped up the alcohol.

These Friday nights continued. Several months after he had graduated to screwdrivers, chest pains returned with half-forgotten painful memories from his college freshman year. This time with a kicker. A new, sharp pain beneath his ribs.

Charles stayed in Saturday and Sunday. He lay on the couch, did not drink, and surfed the net. His breathing returned to painless inhalations. He scolded himself for being a worrywart.

That began a cycle of binge nights followed by skeins of recovery days. Several months passed. Rest lessened his chest pains, but slowly he realized the pain under his ribs never completely disappeared.

One Saturday morning, after closing the bar the night before and unable to sleep, he finally dozed off at dawn, uncomfortable on the couch. A sharp rap on his condo door woke him. He ignored it, but the insistent rap repeated. His boss called out that she wanted to talk to him. Charles didn’t answer. She found his key in the planter by the door. She opened the door. “Come on. Get up. That’s some hangover.”

He didn’t try to sit up. Without opening his eyes, Charles lifted his right arm a few inches and slowly wiggled his fingers.

She realized that was his limit this morning. “We need you at work. This week’s coupon circular reads like crap.” She shifted his legs to the floor and helped him to sitting position. “You’ll feel better with some good food.” But when she maneuvered him into her white Mini Cooper, she drove straight to the hospital.

His diagnosis was two-fold. Fluid buildup in the lungs and kidney disease. The doctors limited his fluid intake and started him on a diuretic. After a few days, he could breathe without chest pain, but inside, under his ribs, his kidneys screamed for attention. The doctors told Charles he had six months unless he got a donated kidney and that he was far down the list.

A few months later, the doctors okayed Charles for the first artificial kidney. “I knew they could do it.” His discharge orders were a strict diet, a max of half-a-gallon liquids per day, and seven hours rest every night.

After recuperation, he returned to work, spent most evenings at home, and was bored out of his mind. He started smoking grass. It took him to his mellow place without leaving his cozy refuge. His new routine: evenings at home, get loaded, drink sodas, and eat sweets. He didn’t allow stomach rumblings to disrupt his pleasure. Though when a red splotch on his stools appeared, he returned to his prescribed diet and rested like a monk. In a few days they disappeared. He banished from thought transient symptoms.

Indulgence followed by days of diet and rest, which he broke as soon as symptoms vanished. This cycle lasted years.

~

A dozen years later, one day at work, his bathroom visit gave him an unpleasant surprise. Copious blood in the toilet, crimson and near black. When he stood, everything blurred. He leaned against the side wall until the dizziness passed. He left work as soon as he felt able.

His general practitioner sent Charles to a gastroenterologist. A colonoscopy removed cancerous polyps, but the procedure also revealed the cancer had metastasized to the liver.

His new prognosis: six months to live.

“I’m not worried,” Charles declared. “They cured my heart with a pacemaker. My kidney was replaced by a better, artificial one. Medical science always comes through. Before six months goes by, they’ll be able to handle this liver problem. Science advances faster than my body decays. I am an immortal man.”

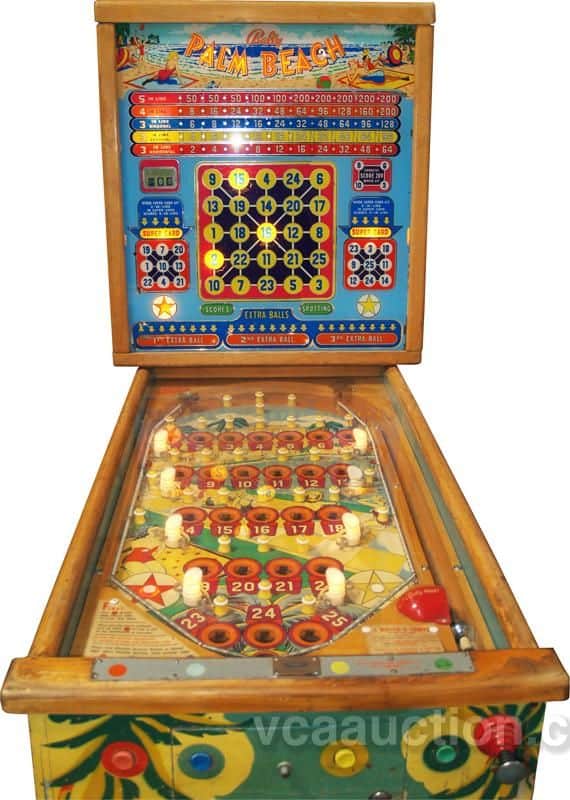

Cyborg Image. Bing from my description