Lessons from ‘In the Cool of the Day’ for Writers

I turned on the TV the other morning to TCM. A movie was playing in which the man was trapped in a relationship with a wife who he had wronged. She used it as leverage over him, to control him and make him suffer as much as she suffered. He had met a younger, more innocent woman—the wife of a friend—who he felt alive around.

This skeleton was so much like the “Wasted Promise” story I’ve got percolating that I had to watch as much as I had time for. What can I learn from that story and how it was told?

I wanted to see how the author built up a credible relationship between the trapped man and the younger woman. In words, in scenes.

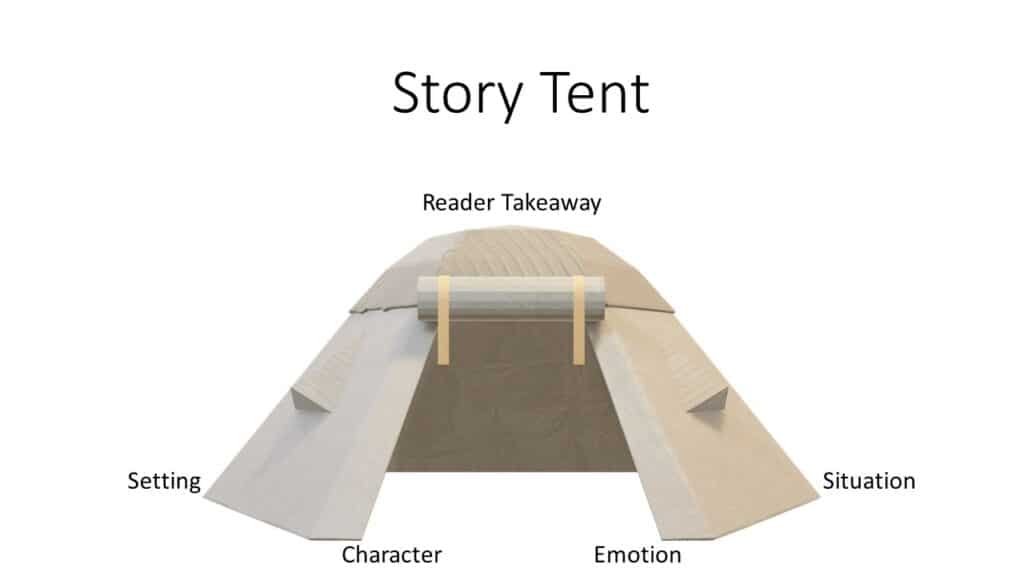

The Story

The movie’s name: In the Cool of the Day, starring Peter Finch, Shelley Winters (his wife), Jane Fonda (the younger woman) and Arthur Hill (the cuckold friend). I got the book from Enoch Pratt and have read half of the Susan Ertz novel (publ. 1960, her name was unknown to me).

Murray Logan (Peter Finch) arrives in America on his first trip, a newly elected member of the board of a small transatlantic publisher. He feels himself to be socially awkward. He visits Sam Bonner, son on the senior partner, at his home in Connecticut. Sam is not in the office due to minor illness, while his father has had a serious heart attack and one of Murray’s missions is to assess how serious the situation is. In the background we discover the publishing company is not flourishing. It’s just holding its head above water.

Murray arrives at Sam’s very comfortable home. Susan Ertz describes the scene in solid, concrete, relevant images. We learn Sam’s marital troubles. His wife went to Mexico to visit her sister. She has a difficult time since her early teens with TB, bronchitis, and such. Sam babies her, insists that she never strain herself or do anything risky. Christine (Jane Fonda), his wife, after leaving her sister’s realizes she cannot stand such a cloistered life. She travels to NYC, but refuses to come home to Sam unless he agrees to let her have more breathing space.

Murray leaves Sam’s house, ready to hate Christine for the distress she causes his friend. Back in NYC, soon thereafter he stops at Sam’s father’s townhouse. The old man is on bed rest, but the nurse allows him to visit, where he finds that Franklin Bonner already has a visitor, Christine his daughter-in-law. Besides the normal chit-chat of the occasional, Murray lets a small zinger at Christine, that he was sorry he didn’t see her at her house when he visited the other day.

Through authorial contrivance, Murray and Christine leave together. She intrigues and repulses him. Then she insists that since he opened the wound of her relationship with Sam, he come on a ride with her and hear her side of the story. Slowly falling resistance in Murray gives way to the spell of her enchantment. He agrees to take her requirements to Sam and see if Sam seems able to change sufficiently to allow her the space she needs.

There is the willing suspension of disbelief, but this was a secondary suspension which I thought not quite successfully pulled off. Why should she accept his assessment, a new acquaintance?

It is much superior to how I could do it. the measuring stick is very tall.

Murray goes to a cocktail-dinner party given in honor of his visit by a good-natured saenior manager in the NYC branch of the firm. His wife is very well-drawn, sympathetic, and interesting. It’s a shame her role is limited so far, in the first half of the book—I’ll be much surprised if she is pulled up in a major way in the second half. He sees the strengths of a strong, complementary marriage, making a nice contrast for the later depiction of his and Sibyl’s home life.

While there, he talks with Sam in depth about Christine’s needs and her demands to come back to Sam. Sam agrees to anything to get her back.

Murray meets Christine, as arranged for Friday lunch, to continue his role as intermediary. She asks and doesn’t argue with his assessment that Sam will make the changes she needs. Then they fall into a deep reverie, ignoring Sam and Christine’s impending rapprochement. At Christine’s urging, he tells her what he has never spoken of to another, the difficult relationship he has with his wife and his role and fault in it.

On return to England, Murray finds that neither his wife nor his mother have any interest in what happened to him while he was in America. No questions about sightseeing, office politics, people, parties. Nothing. But Christine writes him letters at the office, which makes him see now that she feels as much for him as he does for her—which calls for another little suspension of disbelief, because in NYC his interest and her interest already seemed perfectly aligned by narrative information.

In a few months, he gets a letter announcing that Sam has allowed her to take a vacation to Europe, alone since he is busy with work. Murray and Christine meet in the Savoy and go to lunch, resuming their infatuation with no real interruption. Christine wants to meet Sibyl. End of 1st half.

Miscellaneous analysis.

Seth, Christine’s dog, ran away while she taunted Sam with her demands and distance from NYC. That was a bit of whimsy that perhaps told Christine she had to return to Sam or that things she relied on, like Seth’s presence, could not be guaranteed.

Martin, Murray and Sibyl’s son, was born mentally deficient after her bout with German measles early on in her pregnancy. She blames Murray’s side of the genetic family for the problem, dismissing t a differing medical opinion. Another piece of non-essential storyline that makes the novel less mechanistic and deterministic than it would be if omitted.

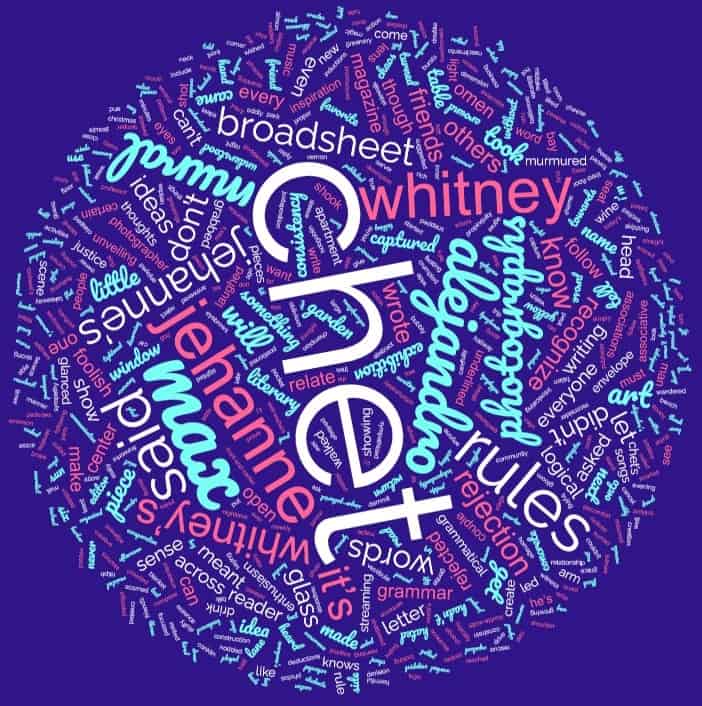

Writing Craft

Susan Ertz published this in 1960. I like her clean style of narration. Does this mean that at 13 (as I turned in 1960) my taste was already formed? And forever more, I will be out-of-whack with literary currents?

Furthermore, I can’t write a lengthy story like this anyhow. In short and flash stories, in addition to my taste, I have an underlying constraint (a subconscious dictate) to never add additional words when those meanings can be inferred from existing words. Susan Ertz definitely was not constrained in that fashion. She would state things from several angles which leads me to reconsider.

Realization

Since I don’t do that, what I am doing forces the reader to assume my narrator worldview and yet not giving enough details to make that worldview firm. That is, putting too much of a strain on the interest and willingness of the reader to suspend interpretation. I need to keep the concern about short story clarity and concreteness.

Disappointed with last half of book – too on-the-nose and melodramatic, with no new insights