Never Be Published

Chet pulled the envelope from the hallway cubbyhole. Its return address, Bay Literary Magazine, excited him. He dashed up the stairs to his third-floor apartment. The sun shone above the townhouses across the wide boulevard. He loved the light of late afternoon streaming through the double-width window onto the bench seat. It was a prime reason he rented this apartment. That and it was near the art scene of Mount Vernon Square.

He tore open the envelope. Skipping the header, he read “Unfortunately.” He crumpled and threw the letter onto the table. After several minutes, he calmed enough to look again at the rejection memo.

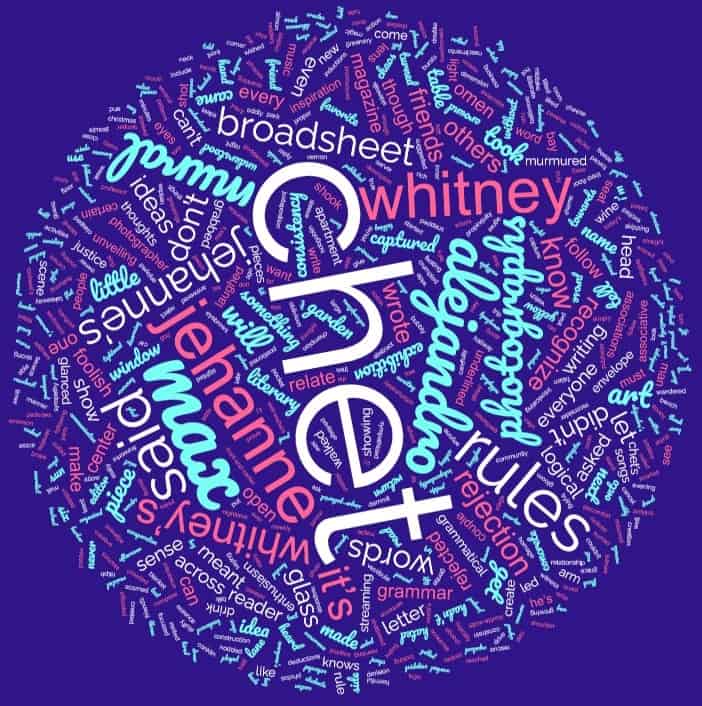

How could his piece be rejected? Everyone praised his broadsheet about the unveiling of Whitney’s mural on the garden wall of the Canton art center. Even Jehanne, a new friend and a photographer of few words, murmured that he had captured the mural’s essence.

The sinking sun shadowed his window. He turned on a light to read the rejection more carefully. The letter was full of underlined phrases. “Cannot follow grammatical rules” was double underlined. It would never be published. Signed, Alejandro.

Why hadn’t Alejandro recognized that he captured Whitney’s inspiration?

“Dammit.” Chet yelled in the empty room. Everyone who knows anything knows what I meant. I’m not rewriting it. I captured the leaps and jumps that Whitney made to assemble her scenes. Grammar! You must break rules to create art.

He had to stop fixating on the rejection. Tonight, the Art Center was featuring Jehanne’s photos at six. Everybody will be there. He didn’t want to cast gloom.

~ ~ ~

An hour later, Chet walked down Conklin Street. Damn editor. He shook his head to drive away unwanted thoughts and focused on the yellow sugar maple in the little park between the streets. Brilliant yellow would blanket the ground in another week.

“Chet.” Whitney, the muralist, called out from a sidewalk table at their café hangout. “Over here.” Next to her, Jehanne sighted him through her lens. Did he not exist if her scope didn’t capture him? Max moved his guitar to allow their friend a good seat.

Chet hurried across the greenery. “Everyone’s here, before the unveiling.”

Max glanced at Jehanne, but spoke to Chet. “Our champion is nervous. Every toast has fallen flat. Your turn. Use magic words to lift her as you did with Whitney’s broadsheet.”

Chet winced, tried to hide discomfort. “Your photographs, Jehanne, freeze dilemmas so others may see them with sympathy as you do.”

Whitney sipped her drink, then said, “The mural visitors understood, not least from your broadsheet, that multiple associations led to concrete groupings of people. You put into words why I painted it.”

Max swooped an arm towards a server, who rushed over a sparkling glass for Chet. “Can’t you write up something for Jehanne’s photographs?”

Chet took a large draw on his drink, so he could compose a response. At last, he said, “You know it’s not that I don’t want to, it’s that I don’t know that I can do it justice.”

Over the din of Whitney, Jehanne, and Max saying he could, Chet said, “I’m so glad my description was well received by my friends and the mural crowd.”

Jehanne’s eyebrows tightened. “I sense a ‘but’ coming.”

I nodded. “But Bay Literary Magazine rejected my broadsheet text. It came in today’s mail.”

Whitney extended her hand. “Let me see that letter.”

Chet took it from his jacket pocket and handed it to her. Max slid close, reading over her shoulder.

“The rejection. It’s an omen,” Jehanne said. “My photographs will be scorned.”

“Not at all. The omen is on my writing. Not an omen of photographs I have not written about.”

Max reached across Whitney and snapped the paper. “This is nonsense. Anyone who creates will recognize the inspiration, even if you broke a few stuffy grammatical rules.”

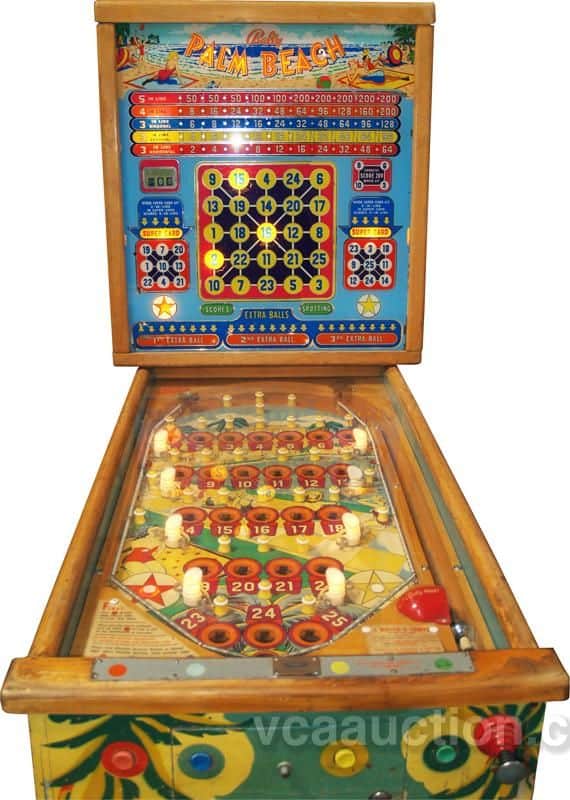

Max turned to Chet. “I recognize Alejandro’s name. When Professor Nascimento hired me to sing a couple of songs at a Christmas party a couple of years ago, his favorite students were there. Alejandro was front-and-center. At the end of my songs, Alejandro told me I pronounced ‘grace’ wrong. I’d forced it into assonance with ‘prove.’ He’s a rich boy who follows the rule that privilege leads to success. To make things worse, he’s not only the editor, but the publisher and owner of the magazine.”

Chet grimaced, then looked at his watch. “It’s quarter to six. Let’s get to the Community Art Center. They can’t open Jehanne’s show without her.”

~ ~ ~

Max played soft music, intoxicating and disarming guests at his friend’s inaugural showing. Whitney glided around the exhibition floor as if it were the premiere stage of Baltimore. She paused at certain photographs, then slipped to the wine and cheese table with others awaiting the exhibition.

Jehanne relaxed after she saw patron smiles and heard one ask how much for her nighttime shot of the Inner Harbor. She chatted with Chet, but sympathized with his ill-ease when well-wishers asked for his broadsheet of her show. She wished he said more than the curt, “I don’t have the skill to do it justice.”

Whitney came to his rescue. “Come with me where it’s less crowded.”

She took Chet to the side vestibule. “Relax. Have a glass of this wine.”

Chet noticed a man had wandered from the exhibition to the outside mural with Chet’s broadsheet in hand. The man walked to the far corner where a singer-guitarist, Max, sang oblivious to the stiff gentleman in the business suit with his hands clasped behind his back. Whitney’s homage to Norman Rockwell’s “Abstract and Concrete.”

Max raced over to them. “You’ll never guess who that is.”

Chet rolled his eyes. “The pope.”

“Alejandro.” Max tilted her head towards the side glass window. “He only glanced at Jehanne’s photographs then he headed to the garden and Whitney’s mural.”

Whitney’s eyes and mouth shot open. “Oh, no.”

Chet started for the garden door. Max grabbed his arm. “You can’t go out there. That would create a scene and ruin Jehanne’s night.”

Chet resisted. “I have to tell him what he can do with his rejection.”

~ ~ ~

“What are you doing here, Alejandro? Looking for something to reject?”

“Do I know you?” Alejandro cocked an eye at Chet.

“My name is Chet Almon. You rejected my piece, ‘Creativity from Chaos’, about this mural you stand in front of. Why did you come?”

He laughed. “Your enthusiasm for the mural intrigued me. I was free this evening, so I came.”

“Even though you hated my story.”

“Hate is too strong a word. Repulsed by your style is more like it, though I enjoyed your enthusiasm. However, your prose violated almost every literary guideline. My readers would cancel their subscriptions if I offended them with such illiterate prose.”

Chet bit his lip, trying to get hold of his temper and to reply sensibly. “Let me get this straight. You liked what I wrote, but you hated the way I wrote it. Don you agree that Whitney built upon the chaos of activities and worked it into a creative mural?”

“Not really, but it’s an interesting thought. It’s a shame you ignored rules of grammar and logical sense. Your piece flitted from idea to idea without showing how they relate.”

“Propinquity.” Chet said with exasperation. “When ideas are adjacent, their relationship is associative. Implicit.”

Alejandro shook his head. “Your sentence construction is atrocious. A piece of writing advice. Show your reader how ideas relate. If you do not, each reader will have their own takeaway of what you wrote. No one will know what you meant. That can never be published.”

Chet snorted. “In return, let me tell you true artists, not people who meekly follow rules, know that creation cannot be explained logically. The juxtaposition of ideas shows that pieces of one notion give rise to the next. Only then is something new and positive created.”

“You should clean up that sentiment and include it in your essay.”

“I showed it in action. The reader must recognize it by its occurrence.”

“Tell you what, Chet. Follow the rules of grammar, make the change I suggested, and resubmit. I’ll reconsider it.”

“Consistency reveals a little mind,” Chet said in derision. It was a favorite phrase that he heard often growing up.

Alejandro laughed. “Get your quote correct. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, ‘A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds’. The word ‘foolish’ adds a dimension to communication that you have missed.”

A hot flush ran up Chet’s neck. Thank god, his friends hadn’t been around to witness this fiasco. Goddammit. Rules constrain you, don’t they? But Emerson’s ‘foolish consistency’ implies only certain rules are harmful.

“Hey, Chet. Hiding out here? You’re not avoiding my lens,” Jehanne grabbed his shirt sleeve and led him to the atrium. Max had resumed a gentle tune to support his friends.

Jehanne positioned Chet next to Whitney, with Max on the right. Jehanne set the timer and took her place, along with a glass of bubbly.

After the group photo, everyone asked Chet about his talk with Alejandro?

Chet didn’t mention his bald mistake. Instead he said, “I asked him, was it logical that Whitney’s mural, Max’s music, Jehanne’s photographs, and my writing arose independently in our little circle? No, I answered for myself. It wasn’t logical, not truly. It was associative, like streaming fireworks that exploded into second bursts.”

Jehanne said, “I don’t understand that. How does that relate?” The others murmured their requests for him to explain.

Chet realized that to make his idea sensible to the photographer and his friends, he had to use words in a manner that made sense to them. Talking was based on rules, though he couldn’t name them all. But if he followed the rules, he would be understood. Rules made his ideas intelligible to others.

Oddly, the memory of driving in the proper lane occurred to him. Following the lane rule meant that car crashes didn’t occur on every trip.

“Let me try again,” Chet said. Would he ever be able to write pieces organized by words, logic, and deductions when his thoughts jumped between patterns, associations, and inductions?

Image of Word Cloud generated with https://www.wordclouds.com/