Party Story, Prose Story

A story is easy to tell at a party. Why is it harder to write a story?

There are two fundamental advantages to verbally telling a story. First, there’s instant feedback on what’s working, what’s not, what’s unclear, and what the listeners like and dislike. Second, the storyteller can adjust the story to the audience’s response.

There is a disadvantage to a party story. The gathered audience often does not want to think hard or to have their beliefs challenged, which prose themes can require.

Readers, as well as those who rarely read fiction, readily enjoy party stories. What can writers do to increase the willingness of the reader to continue on reading?

The Writer Must Anticipate the Reader Reactions

In written stories, we must answer questions before the reader has formed them. We fix our responses in text when we compose the story Will the reader be satisfied with the information placed where we put it? Might we offend some readers because our prose contradicts something he already assumed? Also, some people mightn’t know a story reference, while others will, and still others might associate different meanings than anticipated.

Such are the greater tasks that the written story must solve.

Composing the Prose Story

Fortunately, challenging stories that would never fly at a party can soar in print.

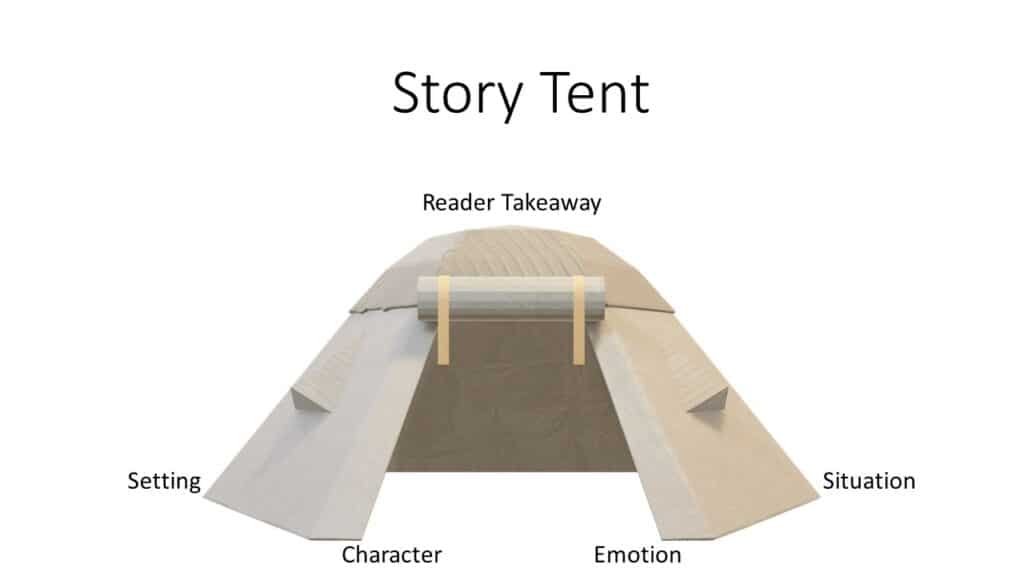

Nonetheless, party stories reveal the essential audience role to the prose story’s success. You must anticipate with craft skills—word choice, sentence structure, and tension escalation—addressing the reader’s questions about background, context, motivations, and meanings.

It’s vexing as well as wonderful that the reading audience has many individuals with diverse perspectives. The writer must refine the characteristics of the audience he plans to reach and restrict his narrative adjustments to meet that targeted niche.

Fortunately, if you write in a genre—romance, science fiction, mystery, historical fiction, and so on—your audience and their expectation are already narrowed and defined.

The knowledge of your audience helps you anticipate the questions they would have peppered you with at a private reading. To the extent you understand your audience. the more accessible and publishable yur story will be.

InfoDump

Addressing your reader’s concerns can lead to the infodump fault, a section of the story where action stops and you explain things they need to know. To resolve this, you need to integrate the facts piecemeal. Don’t tell your reader the background information until it is essential for understanding the action. Often, your story will include a supporting character who is ignorant of the facts in the infodump. When action or dialogue reveals the fact to that character, your reader will learn it too. The reader will follow the character search for sense in the story and not begrudge the lack of earlier information.

I know about infodumps. They have creeped into more than one of my stories.

Ambiguity

Prose stories often have themes and situations that present the reader with an enjoyable contest. In such cases, the writer does not lay bare answers to all the questions a party crowd might pepper one with, instead the reader actively engages with the story by identifying with a character and rounds out the milieu with their own perspectives.

Upon the story wrap-up, the reader evaluates whether they were fairly challenged as well as rewarded for their efforts. Ergo, in creative stories, we sometimes do not answer reasonable reader questions until the very end, if at all.

My overall takeaway is that my sci fi, coming-of-age, and relationship stories have audiences of distinctive traits—beliefs and worldviews. I must delineate the specific audiences more sharply to anticipate where, how, and when I should offer unknown background, setting nuances, and motivation oddities.

Party Image. David Shankbone, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

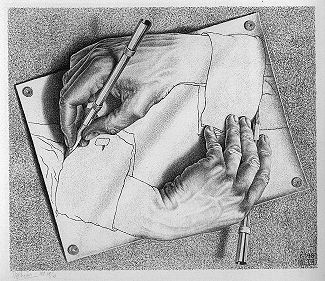

Hands Drawing Hands by M.C. Escher, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3475111