Too Old to Learn

I’m a technical manager of programmers. The job fits me fine. I was brought up in a house where only work was encouraged. At home enjoyment was tolerated, but only if it didn’t interfere with work. At Consolidated Intercommunications, with our communal interest in technology and shared goals, I found it possible to make acquaintances and occasionally friends. It also suited me that work was far from the harsh streets where you got ahead only if you pushed someone else down.

Back in the 1990s our systems ran on IBM mainframe computers. We had PCs but they acted as terminals when we supported Big Blue applications.

Half of the staff were single, under forty, and avid for the latest technical gear. The other half were married, under forty, and interested in their paycheck. Occasionally a person comes on staff who doesn’t fit either typical mold.

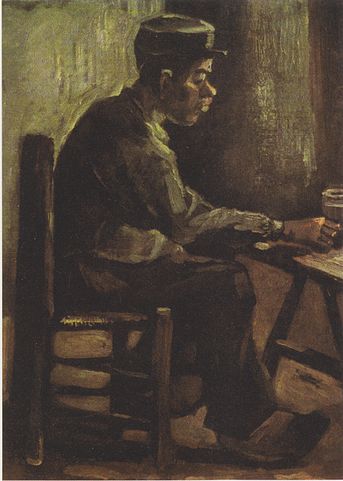

Today I’m expecting such a person. Barbara Jeffers recently completed a Retrain Women program at Goucher College. She graduated from there with a math degree twenty-five years ago according to her resume. She taught high school math for several years until she quit during her first pregnancy. She raised that child and then a second. At Retrain Women, she received excellent grades in Cobol programming and mainframe utilities.

I expected a grandma type at the guard’s desk, but she surprised me. Although a decade older than me, she obviously took care of herself. She dressed carefully. A slim, blue skirt topped with a white blouse. She was quite attractive, Okay, I’m shallow when it comes to evaluating women. The better looking, the easier it is for me to like them.

After hellos, we took the elevator to my office on the top floor of the suburban tower. The four of us managers each had an enclosed room with a door. I pointed to the circular desk with three chairs.

“Have a seat, Ms. Jeffers. Let me check my messages, then I’ll be here now.” I pointed to a plastic plaque on my credenza: be here now.

Her eyes roamed over the manuals in my bookcases.

It only took two minutes to know that the phone messages didn’t need immediate answers. I bounced back several emails with yeah or nay responses. I ripped open a mailer that contained a systems operation text and placed the handy little brown notepad labeled Amazon by my phone. I returned my attention to the new staff member.

“Barbara, let me try to give you a picture of your new job. You’ll be one of seven programmers. We support three major systems. I’ve put you on construction with another woman. Â You ready to get started?” Â Â

“Yes,” she said positively, “but I hope you won’t expect too much of me, Jim. I did well in my classes, but here things might be done differently than the way they taught us.”

I nodded and laughed. “That may well be true and it may be you can show us the right way to do some things.”

“No,” she shook her head. “I’m serious.”

“I’m serious, too.” I wanted her to be forthcoming with ideas, even when she was unsure. “I like to start new programmers with the nightly schedule. It’s a good way to learn the jobs we do and how they work together.”

She opened her purse. “Let me take notes.” Out came a pen and notepad. She nodded for me to continue.

“Notes are fine, but you’ll want to do that with Sandi, when she gets in. She’s up on the details, like middle-of-the-night calls. Tech support lets you know when a job updating the engineering projects abends.”

“Abends? Engineering? Isn’t the system construction?”

“Okay. Okay. Let me explain. Abend. That means the program fails. It abnormally terminates. It abends. Blows up.” I paused, deciding what to tell her without excessive detail. “Unfortunately jobs abends, more than you’d expect. Certainly more than the big bosses expect. The abend rate is the prime item reviewed on my monthly status report. A bad rate, a low bonus.

“Engineering projects. We support the construction department which delivers telephone service. That means central offices, building, maintaining, and connecting. Base switches, plugins, and cables. The headquarters staff, that you get to know and love, are engineers. IT—me and now, you—are on the IT staff. Our systems, our programs track how much, how fast company money is spent on each construction project. The financial information comes to us from another IT staff, down on the fourth floor.”

A quick glance revealed that Barbara took smooth, clear notes. She sat with determined attention. Back straight, notepad perched on the chair arm. Her focus was very appealing. It reminded me of my years in software engineering classes, total immersion in challenging material.

“Don’t worry if you don’t understand everything right away,” I said. “That’s what on-the-job training is for. A chance to learn in context. You already know coding. Now you’ll see how our users track the progress of their hundreds of projects, spend hundreds of millions of dollars, and make sure each year’s objectives are accomplished. You’ll also learn how engineers make our lives miserable.”

Barbara’s head jerked back. “I expect to work hard, Jim. In fact I prefer it, but being miserable is not something I expect.”

“Oh, you won’t have to,” I said, without complete honesty. “That’s in my job description—put up with impossible demands from irrational users. The other half is to make sure you have the tools and time to do what I have agreed to provide the engineers.”

“Irrational users? I’ll be dealing with customers?”

“No, no. We don’t work with subscribers. Our user is the construction department. The engineers.”

I gestured toward her coordinated outfit. “Since we don’t interface with telephone customers, there’s no need to dress formally. You can dress more casually in the future.”

She stretched her neck up, surprising me with a memory of a zoo ostrich. “I take this job seriously and want to be taken seriously myself.”

“That will depend on your work, not your dress. Dress as you feel comfortable. It’s up to you. I don’t usually wear a jacket around the office, but since it’s your first day, I dressed up.”

I stood up signaling my end of her orientation. “Let’s introduce you to your coworker, new best buddy, if she’s in.”

We walked from my office around the corner to the next aisle of shoulder-high cubicles. I stopped at the middle cube and rapped on the divider. “Sandi, the new programmer is here.”

Sandi, a very attractive young woman cradled the phone. “Well, fix it,” she said. Casually dressed in faded jeans and tight tan sweater, she tapped the keyboard with her pinkie. Her long, painted forefinger nails were to accent her look, not to use. She covered the mouthpiece, “Production Support disastered my job with their fix. Just a minute more, I hope.”

Barbara and I stood there. We shared an awkward smile. Be patient I tried to communicate telepathically. Barbara’s eyes shifted back to Sandi. She lifted her eyebrows. I imagined she disliked her coworker’s work attire.

Sandi hung up, typed a final keystroke, and turned to us. “All done, if they do their job right. Run our job now that financial finished their monthly.” Sandi swiveled the seat of her chair towards us. “Hiya.”

“Sandi, please greet our new staff member, Barbara. She recently completed the Goucher Women Retrain program. I want you to introduce her to the nightly schedule.”

Barbara stepped forward and smiled.

Sandi rose. “Aren’t you too old for programming? There were no computers back when you went to first went to college, were there?”

“That’s true, but one is never too old to learn.” Barbara handled the jibe easily. She tentatively put her hand forward.

Sandi leaned forward, as for a hug. They ended with a insincere handshake with Sandi protecting her elaborate fingernail paintings, done biweekly for fifty dollars if I could believe her.

“Lucky you,” Sandi said retaking her chair, “coming back to work. What I wouldn’t give to be at home, lying about, never having to do his bidding.” She nodded at me, “or fix Production’s screw-ups. That would be the life.”

Barbara almost laughed aloud, but she covered her mouth and coughed into her hand. “I raised my son and daughter. That was my job for two decades. It was lovely, but time-consuming and costly. We’re happy with the result. Now I plan to make money so we have something in the bank when Ken retires. Do you have children, Sandi?”

I half-listened as I reheard the latest escapades of her toddler, Bobby. Later I would have to learn the full story of last night’s production run.

Over the next month, Barbara and I became work friends, doing cafeteria lunch most Wednesdays. She talked of her family. I nodded, not revealing that my home life consisted only of books, TV, and movies.

Her husband had a decade before retirement, when they wanted to move to Ocean Pines. They vacationed at a rental there each summer, knew everything about the community and lifestyle, and loved it. Now with her son and daughter both away in college, Barbara wanted to put her considerable energy and multiple talents to work building retirement accounts.

She responded amiably to any work topics I raised. Sandi had instructed Barbara on the monitoring of the nightly schedule. Those programs ran every night, except Sundays and holidays. One stream applied all the daily work accomplished on projects to a main database. The other stream took the bills and payments handled by the financial staff and updated the construction costs billed and paid.

I made sure Barbara realized that corporate decisions as well as construction work assignments depended on the accuracy of that database. She smiled and observed, “A valuable task I am fulfilling for the company.”

In less than two weeks, Barbara felt comfortable to insist that Tech Support call her, not Sandi for nightly problems. When Sandi took the schedule over from me, she told Tech Support to call me. I had to get a buddy to remove my number from the callout list.

I monitored Barbara’s progress. She did well with it, but middle of the night calls were inevitable. Learning under stress made the lessons last. Some problems gave data insight, such as costs applied to the wrong project. Others revealed employees reporting hours to projects that were no longer active. Most revealing for programming were abends in COBOL code. Then the code had to be examined, the problem found and fixed.

At lunch, one Wednesday, Barbara announced, “Jim, we have to rerun the entire financial stream before tonight’s schedule.”

It was chicken fajita day in the cafeteria, my favorite lunch. Reluctantly, I rested my fork. “Why am I just hearing about this now?”

She raised her artistically drawn eyebrows, a similarity with Sandi’s fingernails I thought. “It as odd,” Barbara said. “Sandi said she’d never seen anything like it. Last night’s schedule finished early. No abends, but this morning the user asked. ‘How come no charges posted last night?’ That got me investigating. I found out that the user staff changed the accounting date to 9/31/1995 instead of 9/30/1995. A data entry error. Sandi’s program rejected the invalid date. All our financial jobs ran but with no data selected.”

“Damn,” I said, but I rejoiced internally. It wasn’t our error. It wouldn’t count in our abend rate. I toyed with my chicken fajita, buying a second to think.

Barbara took a final bite, then pushed her Caesar salad aside. “The typical night lately has been four to five hours, but only the financial path needs to be rerun. The construction side doesn’t need to be rerun. I estimate two hours.”

“Did you check that with Sandi?”

Her eyebrows shot up rather than arched. Wrinkles under them revealed her maturity. “Sandi wanted me to rerun the entire schedule, but I proved that finance and work activities were absolutely independent. Reluctantly, she agreed the entire schedule was unnecessary. Of course, the final comparison reports will need to be rerun.”

“You convinced her …” I said, wonder lit up certain of my preconceptions, “if it goes wrong …”

“If it goes wrong, it will be for another reason. Not because the job order caused it.”

After another careful bite and slow chew, I said, “I don’t know.”

Barbara rose up. “You put me in charge of the schedule. Let me do the job. I will double-check that Richard Richardson has put the proper date in now. Then I will kick off the schedule. Since it’s the middle of the day when all the staff running jobs, runtime may be erratic. If it’s not finished by quitting time, I’ll continue from home. I have frozen tonight’s schedule and won’t release it until this catch-up run completes successfully.”

Pleased with her intelligent action and decisive approach, I nodded. “Excellent. I love your attention to details.”

“Thank you,” she paused then continued. “Does that make me merely an efficient drone? When my planning is too much for Ken, he acts like I’m just being an efficient drone.”

“Not at all. You learn and adjust quickly.” I thought better about commenting any further on their relationship.

Barbara readied to leave. “I will be kicking off the schedule as soon as the users have fixed the date.”

I nodded, but my favorite lunch still called for my attention. “I’ll see you upstairs. Please update me before you leave for the day.”

“I would never neglect that,” she said, walking away.

I didn’t say what I thought. Sandi didn’t always give updates even when she promised to. More than once, I had to call her home.

Weeks flowed by at work. We got through that user date snafu. In fact, over the following days, Barbara coded a date verify and notify routine. She tested and proved that it handled all date entry errors.

During the first November staff meeting, Sandi reported the change requests were coded and “ready for testing”, but doubted if all possible conditions could be tested before the scheduled Thanksgiving weekend release.

I added Barbara to release testing, mentioning her date fix-up. Ignoring the dissatisfaction that flashed across both women’s faces, I mentioned that end of year bonuses were coming up.

Monday of Thanksgiving week, across the top of cube walls, the sound of irritation clambered down my corridor. To ignore it would be to allow it to fester and grow.

Barbara stood in Sandi’s cube. I stopped at the doorway. They stopped talking when I arrived.

“Ladies, how’s it going?”

Sandi pointed to her phone. “My husband just called. He was in a car accident and is at the hospital right now. I have to go there and make sure he’s alright.” Then she turned her attention to Barbara. “And Barbara says she can’t be responsible for the release testing.”

“That is not what I said,” Barbara corrected her. “I said that fixing any code problems would be in your code and as you haven’t explained them, I can’t be responsible for fixing them.”

“Sandi,” I ignored their argument, “your husband is more important than any release. Go to the hospital. Pick up your son from nursery school if that’s needed. Go.”

As soon as the words were out of my mouth, she grabbed her jacket and walked away. “Thanks,” she called over her shoulder to me, “I’ll call you, when I know how serious it is.”

I looked at Barbara. “I’ll help you if problems come up.”

Barbara grabbed a binder that lay in front of Sandi’s monitor. “I hope her coding notes are more thorough than her on-the-job explanations.”

“Barbara, what are you upset about?” I stared at her. “It’s her husband who could be seriously hurt.”

She shook her head. “I don’t fall for her explanations. Young and cute only sways guys. You didn’t hear what I heard. I was at her desk when her husband called. He didn’t get hit by another car. He ran into their garage door. Her first question was ‘How much have you been drinking?’ His answer didn’t satisfy her.”

I heard this without surprise. Sandi’s home life was chaotic. That was a given. “Give her a break. She has a difficult home life. Her husband’s in the hospital.”

That didn’t satisfy Barbara. “I bet. She made her life what it is. Everybody makes their life what it is. Why do I have extra work because she picked a lousy mate.”

I didn’t think that way, but that was beside the point. “Barbara, come on, accidents happen. People here may make choices you don’t agree with, but they’re your coworkers, not your bosom buddies. You must adjust. Some things are beyond your control.”

She didn’t seem mollified, but I didn’t care if she was. This was work. “Get started with the test scripts. I’ll be in my office if you need me.”

Later that day, when I grabbed a cup of coffee, I walked down my programmer aisle. Barbara huddled with a friend from another project. When Barbara pointed into a program listing, they nodded in agreement. At close of business, Barbara gave me the go status for the release.

At the first December staff meeting, I congratulated Sandi and Barbara on the successful release.

Sandi nodded. “Thanks. Coding to the new accounting fields can get quite tricky, but it worked fine.” She gave a little head bob to Barbara. “Barbara did a good job on proving the mapping worked.”

“Yes. I only had to tweak two pieces of code, Jim,” Barbara echoed with a twist, “while Sandi was unavailable.”

The first Tuesday in January, I received official confirmation of bonuses. It was barely eight o’clock in the morning. No way Sandi would be in her cube this early. She was rarely in until after 9:30 when she dropped Bobby off, but I knew who would be in.

I tapped on another cube entrance. “Good morning, Barbara. Do you have a few minutes?”

She nodded and closed the file she was working on. “What can I do for you, Jim?”

“Nothing like that.” I handed her a paper slip with her bonus number and rating. “I think you’ll be pleased.” I watched her face as she digested it, but I could read nothing special in her attitude.

She stood, placed the slip in her center drawer, and smiled. “Please amplify. What does this mean?”

I took her side chair. “I’m quite happy with your performance. The bonus reflects that. Despite an initial bump with the Thanksgiving release, everything else has been very good. Since you’ve been on staff only six months, the bonus is prorated accordingly.”

She drew back. Her eyebrows furrowed. “What do you mean ‘bump’?”

Her response had come back fast, with a sharp edge. I had struck a nerve. She needed time to control her reactions, so I extemporized.

“Before I answer that, do you have any question about the bonus?”

“No. It’s an adequate start to our retirement fund.”

I nodded. “Then let me start with your ranking, G Plus. Good Plus. In the short time you have been here, you have mastered the daily and monthly construction schedules. You have shown the programming skills necessary to handle Change Requests. Good indicates basic capability.

“Plus, because you show initiative, excellent attention to detail, and care in avoiding problems. These are characteristics I wish everyone had. Not all the staff is capable of that. However, you resisted helping out when Sandi had a problem.”

Her eyes widened, the milky white showing around dark irises.

“You hold it against me that her ill-advised choices interfere with our work!”

I resisted an immediate response, hoping she would realize how judgmental she was.

“What I mean,” she eventually amended, “is that it took me a couple of minutes to realize I had to adapt for her mistakes.”

I wagged my head slightly, not in agreement or disagreement, but to indicate the conversation was over. Despite her age and other skills, she hadn’t grasped empathy.

Standing, I said, “Let me see who else is ready for their bonuses and feedback.”

During the short month of February and into a rainy March, Barbara and Sandi talked only when work demanded. Casual swapping of techniques or information sharing didn’t occur; however, the work got done. I stayed out of it.

Until one Tuesday in early April, Sandi stormed into my office, followed by Barbara.

“She,” Sandi indicated Barbara with the punctuation of a blue fingernail capped with a white fleur-de-lis, “wants me to cover for her tomorrow afternoon which I’m happy to do, but I have to pick up my kid at five no matter what. So if her tests fail, she’s on the hook, not me.”

I suppressed an eye roll. Instead I turned to Barbara who had never asked for unscheduled time off before. “What’s up? We just had our staff meeting yesterday. Nothing of this was mentioned.”

“The doctor’s office just called,” Barbara said. “They had to move my scheduled Saturday appointment to tomorrow afternoon. I asked Sandi to run my test scripts after she completed her data loads.”

“Sounds reasonable,” I said, “and Sandi you just said you could.”

She shrugged her shoulders. I couldn’t stop myself from noticing Sandi’s bouncing bosom.

“Yeah, I can,” she acknowledged, “but fixing her errors may not be possible right away.”

Barbara stiffened. “If my scripts fail, it will be due to errors in your load programs.”

Before Sandi could respond, I interjected. “Ladies, I don’t see the problem. Let’s not borrow trouble. Sandi, you run her tests. Both of you send me bullet points on testing before start of day tomorrow. Now go, so I can attend to my other projects.”

The next Tuesday Barbara came into my office. “Jim, the doctor just called. I have to see her this afternoon. In fact, I’ll be out for the next ten Tuesday afternoons. I can make up the time on weekends.”

I patted the side chair. “Explain, please.”

Her normal smile became a grimace. “It’s absolutely unfair. After all my careful living and sensible decisions, my test result was not good. The doctor made a strong case for chemo which I have decided to accept.”

“Sh——t. I’m so sorry to hear it.”

Her nod acknowledged my concern, but she didn’t offer any more information.

“Of course, you have to do what’s necessary for your health.” My digital world couldn’t lock the world out completely. “We’ll pitch in to cover. Don’t even consider coming in on Saturdays. I’ll find a time code to cover you for time you miss.”

She switched the focus. From our Wednesday lunches, I knew her skill at controlling her half of the conversation.

“The schedules and my new programs will not be a problem, but the users will notice that I’m unavailable for their requests on Tuesdays.”

“True,” I said, “Sandi will have to do that. Schedule changes will go to her when the users can’t find you. Undoubtedly, some will end up with me because they can’t find her.”

Barbara slumped a bit in the chair. “I hope she can handle it.”

I guessed she meant something different—she hated to ask for help. “Sandi,” I reminded her, “used to handle the schedule every day, before she moved to change requests and releases. A little extra work isn’t going to kill her.”

Barbara stood up. “Thank you, Jim. I need to thank Sandi too.” Her serious look turned contemplative. “Bad things do happen to good people.”

1 thought on “Too Old to Learn”